This Down Syndrome Day, we wanted to look at the progress made on meeting communication needs of children with Down Syndrome. In the early stages of development, kids with Down Syndrome show limited means of expressions compared to their peers. However, research and studies over the last two decades have shown that AAC helps children with Down syndrome develop better communication skills than their peers who are not exposed to AAC.

Further, research also shows that early exposure of children with complex communication needs (CCN) to AAC minimizes the potential for continued delay that these children face with developing language. In a 2010 study (Drager, Light and McNaughton, 2010), it was found that AAC intervention can have a positive effect on functional communication skills, challenging behaviour, language development (both receptive and expressive), and speech production. Unlike other studies that observed the effect of AAC on children between the age of 3 and 5, this paper specifically focused on understanding the effect of AAC exposure on children under the age of 3. The study recommends AAC intervention by the age of 6-9 months when a disability with the risk of communication risk is identified. That said, many caregivers still have doubts about using AAC. We looked at some of these doubts on using AAC for children with Down syndrome and asked: are they real, or are they myths?

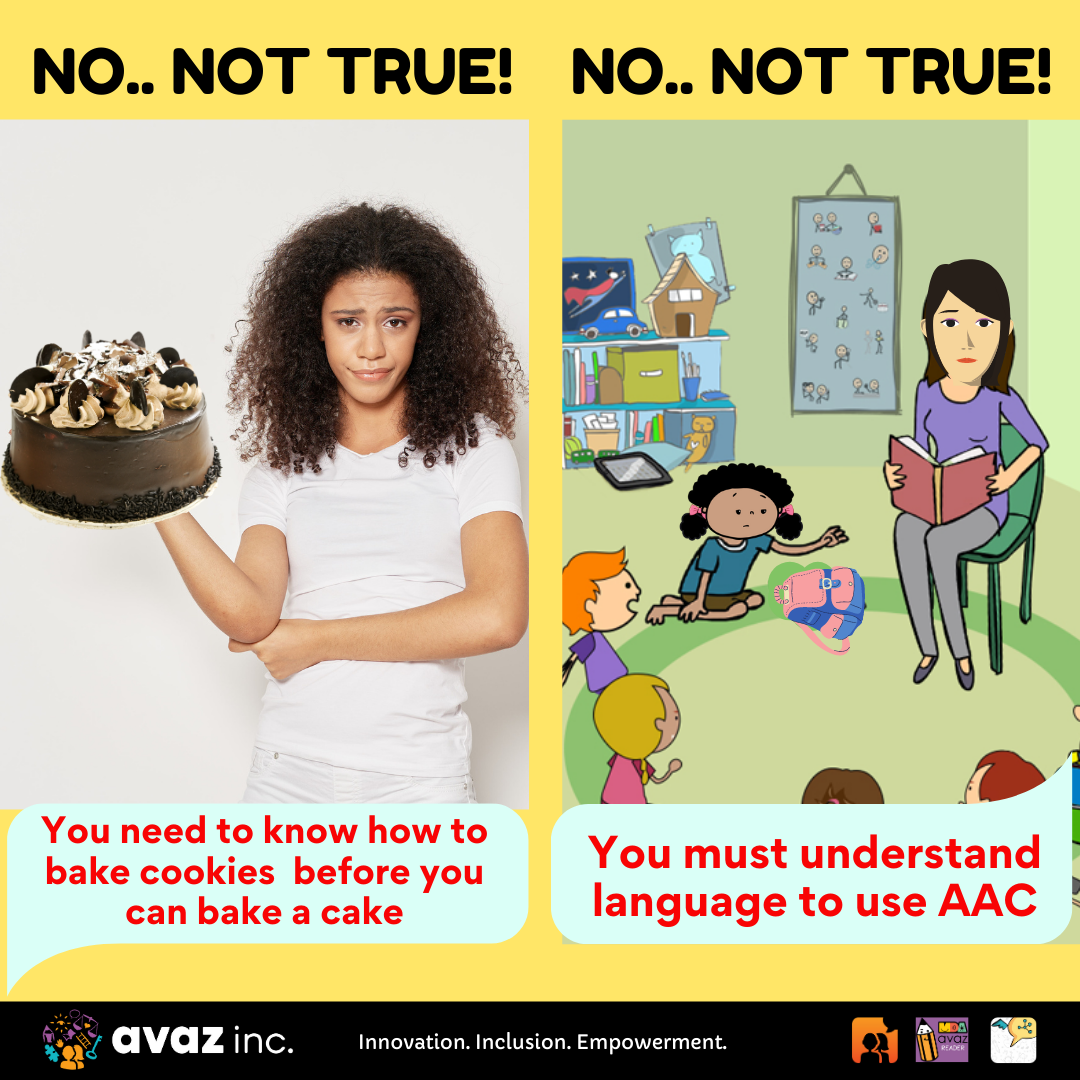

Common myths about using AAC for children with Down syndrome:

1. Fear of natural speech development being impeded

The fear of AAC intervention becoming an impediment to speech is quite widespread. However, several studies (such as Millar, Light, and Schlosser) show that AAC does not cause impediment in the development of natural speech in individuals with developmental disabilities. On the contrary, children with exposure to AAC learn to use multiple modes of communication, unlike children with no exposure to AAC.

2. Fear that social skills won’t develop

Another common fear with using AAC intervention is regarding the development of social skills. How will the child learn social skills using AAC? This fear too is ill-founded — AAC as a multi-pronged model of communication uses modeling, practice and feedback to teach the child different language skills as well as social skills that are required to engage with people (for example, turn taking). Multiple studies have shown this to be effective specifically for children with Down syndrome, including the study by the Janice Light & Kathyrn Drager in 2010.

3. Concern that AAC cannot help tackle challenging behaviour

Sometimes, caregivers question the possibility of resolving challenging behaviours using AAC. On the contrary, though, device-based AAC systems can especially be useful in helping with handling challenging behaviour, by working on Functional Communication Training (FCT) with children. For example, caregivers may model with the child on using a specific AAC switch or symbol, to replace a challenging behaviour like hitting his head on the wall to call someone. Studies show that such methods have been effective with most children observed.

4. Concern that the child will be unable to communicate when the AAC device is unavailable

With advancements in technology, electronic device based AAC systems have become the order of the day. This often makes caregivers wonder if their child will be left stranded without any means of communication when he or she does not have access to the electronic device. Will the child’s communication become device-dependent? If AAC is properly introduced, this is not a major concern. There are many different types of AAC systems, including unaided and aided systems. While unaided systems usually include signs and gestures, aided systems include picture boards, communication books and electronic devices. If a child has no access to an electronic device based AAC system, and if they have been properly trained to use multiple modes of communication, they will not be left stranded: unaided systems, or other aided systems with similar visuals as the child’s device, may be used to communicate with the child.

In our experience, we have heard a lot of success stories of children with Down Syndrome using AAC. Do you have any to share? Leave us a comment!

References:

1. Effects of AAC intervention on communication and language for young children with complex communication needs by Kathryn Drager, Janice Light and David McNaughton, (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4fde/36329edf21ce59bf0afb2a0f7adb10ff00cf.pdf)

2. Effect of early AAC intervention for children with Down Syndrome by Janice Light and Kathryn Drager (http://aac-rerc.psu.edu/_userfiles/file/Light%20ASHA%202010%20%20AAC%20and%20children%20with%20Down%20Syndrome.pdf)

3. Millar, D. C., Light, J. C., & Schlosser, R. W. (2006). The impact of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on the speech production of individuals with developmental disabilities (Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 248-264.)